“We’re so trapped inside our reality that it is inordinately difficult to realize we’re trapped inside anything.” – David Eagleman, The Brain: The Story of You

What does it mean when we say something is “real”? Perhaps it means that we can touch it. Maybe it means we can see it. Some would argue it’s real if we can feel it, and many more would argue that if we can hear it, it must be real. Perhaps in order for something to be real means it exists independent of us; so even if we aren’t there, it will still be there.

But there are enormous differences in the way we experience the world. This is a difference of qualia, or subjective experience. We can’t map our experiences neatly onto the experiences of others. That is to say, there is no objective experience.

“You don’t perceive objects as they are. You perceive them as you are.”

For example, you would probably say this is a star. But I see a Baha’i symbol, which reminds me I was brought up in a Baha’i family, and that rouses a cascade of emotions and memories. Unless you also grew up in a Baha’i family, you would glance at this without thinking about it much at all.

But apart from qualia, there must be an objective world out there, right? Surely, if I disappear, the world will still go on, existing as it always did and always will. In a few short moments together, we will realize this isn’t the case at all. Not by a long shot.

What happens when we take ourselves out of the equation, when we separate the subject from the supposedly “real” object? Well, we find that in reality, there is no unified reality.

Let’s look at what happens when we sneak past the five human senses and observe what remains. What is left of reality if we strip it of sight, sound, touch, smell and taste?

We would find something completely bewildering: there is no such thing as colour, sound, sensation, smell or flavour. Now for the people in the back: colour does not exist. Sound does not exist. Scent does not exist. Sensations do not exist.

How is that possible? Don’t my ears hear, and don’t my eyes see?

Sort of. Our sensory organs detect raw data in the form of photons, air compression waves, molecular concentrations, pressure, texture, and temperature, all of which are computed into the brain’s universal currency—electrochemical signals in the brain. These signals sprawl into networks of neurons (the brain’s most prevalent cell type), signalling cells of the brain to orchestrate what we perceive.

“Our experience of reality is the brain’s ultimate construction. Everything you experience—every sight, sound, smell—rather than being a direct experience, is an electrochemical rendition in a dark theatre.”

What if I told you that you are creating what you see? When you look at something, sensory information in the form of photons are processed through the thalamus at the front of your brain, connecting to the visual cortex at the back of the brain. But at any given time, there are ten times (TEN times) as many connections going from the visual cortex to the thalamus, imposing on reality what we expect to see before we see anything at all. The thalamus then compares what it expects to be there versus what is actually there, and ultimately, the only data that is relayed to the visual system is the error between expectation, and well, “reality”.

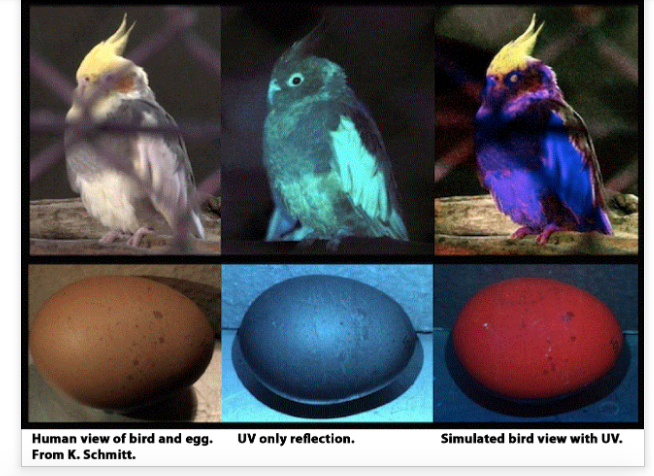

And what about colour? Humans perceive electromagnetic radiation: wavelengths of light reflected by objects. Colour is our brain’s language—it is a way of reading wavelengths, but colour is only generated inside of our heads once wavelengths have been processed. In the outside world, no such thing as colour exists. And in fact, humans can only interpret a small spectrum of wavelengths, what we call “visible light”. This spectrum is only one ten-trillionth of the entire electromagnetic spectrum, or colours that could be perceived, just not by us.

And sound works the same way. I was once perplexed by the age-old thought experiment, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?”, thinking, well, of course it does. But in “reality”, of course it does not. The fall creates movement in the air; compression waves that can be picked up by a perceiver with the right machinery. But if no one is there to hear it, it cannot be heard.

So what does exist? Well, a perceiver who creates a reality between its ears.

In What is it like to be a bat? American Philosopher Thomas Nagel discusses the impossibility of occupying another creature’s reality. Reality for a bat is confined to the information it picks up through echolocation of air compression waves. Every creature has a different machinery for perceiving reality: dogs perceive wavelengths of sounds that humans cannot, and fish are certainly not perceiving sounds as humans do.

“Bat sonar, though clearly a form of perception, is not similar in its operation to any sense that we possess, and there is no reason to suppose that it is subjectively like anything we can experience or imagine. This appears to create difficulties for the notion of what it is like to be a bat.”

Although a bat can’t see a tree and call it green, it most certainly won’t choose to fly through it, nor would it be able to. And a dog, while it doesn’t see the vibrant green leaves, still sees that there is an object blocking its way. So, in reality, is there a tree?